Climate Change Science

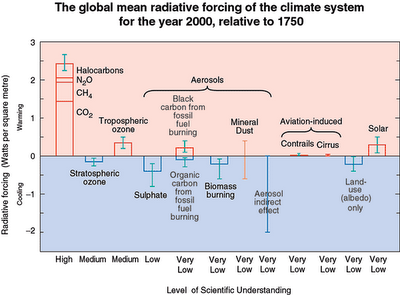

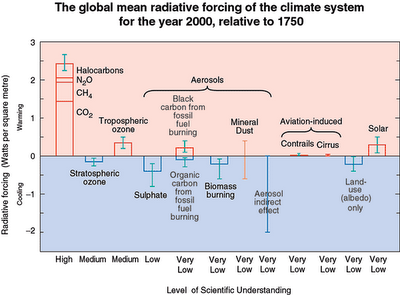

This post covers the science of global warming, as I understand it. The graph above is one of the most instructive to be found in the IPCC report on climate change. It will make more sense after reading what follows. The IPCC makes the following notes on it: "

Figure 3: Many external factors force climate change. These radiative forcings arise from changes in the atmospheric composition, alteration of surface reflectance by land use, and variation in the output of the sun. Except for solar variation, some form of human activity is linked to each. The rectangular bars represent estimates of the contributions of these forcings - some of which yield warming, and some cooling. Forcing due to episodic volcanic events, which lead to a negative forcing lasting only for a few years, is not shown. The indirect effect of aerosols shown is their effect on the size and number of cloud droplets. A second indirect effect of aerosols on clouds, namely their effect on cloud lifetime, which would also lead to a negative forcing, is not shown. Effects of aviation on greenhouse gases are included in the individual bars. The vertical line about the rectangular bars indicates a range of estimates, guided by the spread in the published values of the forcings and physical understanding. Some of the forcings possess a much greater degree of certainty than others. A vertical line without a rectangular bar denotes a forcing for which no best estimate can be given owing to large uncertainties. The overall level of scientific understanding for each forcing varies considerably, as noted. Some of the radiative forcing agents are well mixed over the globe, such as CO2, thereby perturbing the global heat balance. Others represent perturbations with stronger regional signatures because of their spatial distribution, such as aerosols. For this and other reasons, a simple sum of the positive and negative bars cannot be expected to yield the net effect on the climate system. The simulations of this assessment report (for example, Figure 5) indicate that the estimated net effect of these perturbations is to have warmed the global climate since 1750."

Let us run through a few conclusions gleaned from the IPCC report on global climate change, focusing first on the scientific basis for believing anthropogenic effects on the climate are real. At a 95% confidence level, the temperature records indicate that the global temperature average has increased by 0.4 to 0.8 degrees centigrade over the past century. The industrial revolution, source of most anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, kicked into gear in the late nineteenth century, precisely the time period when temperatures began to rise. By the way, the instrumental record for climate observations begins in 1861.

There is a greater than 90% chance that snow cover has decreased at least 10% in the last 40 years. That a few areas of the globe have not warmed according to the records does not diminish the significance of the overall trends and averages--it is well known that within recognized global climate trends will be found regional and local exceptions and countertrends; this is due principally to unique geographical factors.

The IPCC report articulates a useful way to think about the climate and the influences which bear upon it:

"Changes in climate occur as a result of both internal variability within the climate system and external factors (both natural and anthropogenic). The influence of external factors on climate can be broadly compared using the concept of radiative forcing. A positive radiative forcing, such as that produced by increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases, tends to warm the surface. A negative radiative forcing, which can arise from an increase in some types of aerosols (microscopic airborne particles) tends to cool the surface. Natural factors, such as changes in solar output or explosive volcanic activity, can also cause radiative forcing. Characterisation of these climate forcing agents and their changes over time is required to understand past climate changes in the context of natural variations and to project what climate changes could lie ahead."The IPCC estimates that carbon dioxide causes 60% of the current unnatural (human-caused) excess of radiative forcing, methane 20%, halocarbons 15% and nitrous oxide about 5%. Carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere have increased about 33% in the last 150 years--it has reached a concentration definitely not exceeded in the past 420,000 years and probably not in 20 million years. A quarter of anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions are traceable to deforestation, the rest to coal, oil, and natural gas usage. The average rate of increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations has been, in recent years, 0.4% a year.

On methane the IPCC reports, "

The atmospheric concentration of methane (CH4) has increased by...151% since 1750 and continues to increase. The present CH4 concentration has [definitely] not been exceeded during the past 420,000 years. The annual growth in CH4 concentration slowed and became more variable in the 1990s, compared with the 1980s. Slightly more than half of current CH4 emissions are anthropogenic (e.g., use of fossil fuels, cattle, rice agriculture and landfills)."

On halocarbons the summary provided is: "

Since 1995, the atmospheric concentrations of many of those halocarbon gases that are both ozone-depleting and greenhouse gases (e.g., CFCl3 and CF2Cl2), are either increasing more slowly or decreasing, both in response to reduced emissions under the regulations of the Montreal Protocol and its Amendments. Their substitute compounds (e.g., CHF2Cl and CF3CH2F) and some other synthetic compounds (e.g., perfluorocarbons (PFCs) and sulphur hexafluoride (SF6)) are also greenhouse gases, and their concentrations are currently increasing." Note that some of these synthetic compounds have enormously high rates of radiative forcing.

On the graph first presented it is worth remarking that the greatest potential negative radiative forcing is aerosols generated by human activity. However, these aerosol are very short-lived in the atmosphere and, moreover, as the graph indicates, the magnitude of the negative radiative forcing cannot be ascertained with any degree of accuracy. If it is small, then we have lost a counterweight to the preponderant positive forcing, one that we might have found it necessary deliberately to magnify in the future. Yet, if it is large, we have still to contend with the observed fact that, in spite of its power, the positive forcings have overwhelmed it to such a degree that the earth is warming, snow receding, etc.

To conclude with the relatively obvious: "

Reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and the gases that control their concentration would be necessary to stabilise radiative forcing. For example...carbon cycle models indicate that stabilisation of atmospheric CO2 concentrations at 450, 650 or 1,000 ppm would require global anthropogenic CO2 emissions to drop below 1990 levels, within a few decades, about a century, or about two centuries, respectively, and continue to decrease steadily thereafter. Eventually CO2 emissions would need to decline to a very small fraction of current emissions." This could be rather challenging without major technological advances in the near future, especially if we want to keep CO2 levels at less than twice pre-industrial levels (ie, 560 ppm), which would require cutting CO2 emissions to 1990 levels within 50 years or so. To achieve such a reduction within that timeframe we would have to hit an inflection point in total yearly emissions well before the 50 year mark. But, with the emerging economies of Asia pressing hard into their industrial prime with their 3 billion people (compared to 1 billion in the first world), and considering the current state of technology, it appears from the present vantage a feat nigh impossible.

The appearance may be deceptive. What is wanted is political will. This is the ingredient we presently lack, more even than technological magic.

But, back to the scientfic evidence for now. The average temperature is projected to rise by 1.4 to 5.8 degrees centigrade over the next century. The range of projections is fairly large. This is due to the manifold uncertainties which necessarily inhere in climatology. The climatic system is so complex, has so many interrelated variables, so many causes and effects and feedback loops, that, in mathematical terms, it is theoretically, and not only practically, impossible for a computer

ever to calculate the variables accurately enough to deliver up a certain prediction of the future of the earth's climate. Instead, what we have to deal with and base decisions upon is probabilities, great systems of probabilities with their attendant possibilities. One of the early climate modelers was sufficiently astounded by the system's complexity that he questioned whether it was even deterministic--"We may never know for sure." Hilarious. A scientist so baffled in his noble quest as to actually question the determinism of a physical system--this is as much as for him to question the first premise of scientific reasoning (that every effect has a cause). Who knows, maybe the climate even possesses free will--

The IPCC mentions also some long-term considerations:

"Emissions of long-lived greenhouse gases (i.e., CO2, N2O, PFCs, SF6) have a lasting effect on atmospheric composition, radiative forcing and climate. For example, several centuries after CO2 emissions occur, about a quarter of the increase in CO2 concentration caused by these emissions is still present in the atmosphere.

After greenhouse gas concentrations have stabilised, global average surface temperatures would rise at a rate of only a few tenths of a degree per century rather than several degrees per century as projected for the 21st century without stabilisation. The lower the level at which concentrations are stabilised, the smaller the total temperature change.

Global mean surface temperature increases and rising sea level from thermal expansion of the ocean are projected to continue for hundreds of years after stabilisation of greenhouse gas concentrations (even at present levels), owing to the long timescales on which the deep ocean adjusts to climate change." The two criticisms of the science of global warming which most impress me are those that focus on the admitted uncertainties in climatic sciences (eg, the unknown magnitude of the aerosol effect) and the temptation for scientists to make arbitrary adjustments in their computer models of the climate so that those models come to reflect the scientists' preconceived conclusions (which means such models would effectively be designed to predict anthropogenically caused global warming because there is near univeral agreement among scientists that this is actually happening--peril of groupthink, a trap to which scientists [and everyone else] are historically susceptible). But, as to the first criticism, we can only work to reduce the uncertainties, for they will never vanish. The related issue of modelling deceptions calls for critical, skeptical, intelligent, independent investigations of the reasoning and data behind the headline predictions.

Labels: climate change science, climate change uncertainties